Parasite made history in 2020 when it became the first film not in English to win an Academy Award for Best Picture. Director Bong Joon-ho’s success is groundbreaking in the conversation about diversity in Hollywood—from the United States’ side. Hollywood may only now be opening its doors to South Korean cinema, but the door has always been open in the other direction. Bong Joon-ho directs with a transnationalist, Korean lens on Hollywood tropes and expectations; his work is part of a long conversation South Korea has been having about Hollywood and the United States’ cultural influence on the world.

Parasite’s unflinching depiction of capitalism, however, is not unique to director Bong Joon-ho’s œuvre. Where Parasite focuses on a distinctly South Korean manifestation of the horrors of capitalism, Okja (2017) takes a broader view, employing a multinational cast that clashes between Seoul and New York. American megacorporation Mirando, led by Lucy Mirando (Tilda Swinton), plans to revolutionize the meat industry with genetically engineered superpigs. As an experiment, the company sends several superpigs to farmers around the world. In ten years’ time, the best superpig will be selected to represent the product at a lavish ceremony in New York. Mija (Ahn Seo-hyun) has grown up alongside her superpig Okja (voiced by Lee Jeong-eun), with whom she has a close relationship. When Dr. Johnny Wilcox (Jake Gyllenhaal) arrives to evaluate Okja and take her away, Mija discovers that Okja never belonged to her and her grandfather (Byun Hee-bong); in fact, she still belongs to the Mirando Corporation. Desperate to reunite with Okja, Mija embarks on a perilous journey flanked by animal rights activists and corporate power players into the wicked heart of American capitalism.

Bong Joon-ho (1969–) came of age in a turbulent South Korea still grappling with the legacy of the Korean War. Anti-American sentiment was pervasive, particularly when it came to the presence of U.S. military personnel. Back-to-back dictatorships coincided with strong pro-democracy demonstrations. As a child growing up in Seoul, Bong became a fan of Hollywood movies he saw on the Armed Forces Korea Network, the U.S. military’s TV channel. When he enrolled at Yonsei University as a sociology student, the pro-democracy movement was reaching its apex, culminating in violent protests often led by student activists. As a student himself, Bong explored Asian cinema; after he graduated, he debuted with Barking Dogs Never Bite (2000), then went on to direct Memories of Murder (2003), The Host (2006), Mother (2009), Snowpiercer (2013), and finally, Okja (2017) and Parasite (2019).

English acts as a symbol of power and assimilation in Okja. Mija’s relationship with English changes over the course of her journey. The movie opens with her and Okja adventuring through a dense forest. The strength of their bond quickly becomes clear when Mija falls off a cliff and nearly plummets to her death, only to be saved by Okja. Tenderly, Mija lifts up Okja’s ear and whispers something to her, inaudible to the audience. She returns to her home on top of a mountain peak, where her grandpa is waiting for her and the superpig evaluation committee. Mundo (Yun Je-mun), a Korean Mirando representative, arrives and takes the data collection box from Okja. As Dr. Johnny Wilcox ascends the final steps and gripes loudly about the trek, Mija is star-struck by the appearance of the world-famous host of Animal Magic. She knows very little English at this point and can only gesture for him to autograph her sash as she says, “Sign!” Even as Dr. Johnny continues to complain, this time about having to be “on” all the time as the face of the Mirando Corporation, Mija’s only reaction is to stare, amused but uncomprehending. An interpreter is already present in this first scene, acting as the symbolic negotiator between Korea and the United States. At this point, Mija is content to engage with English, as it is nothing more than a visitor on her doorstep.

English’s role as a symbol of power becomes more obvious in Okja’s initial rescue. When Mija learns that Okja is being taken away to New York, she goes to the Mirando office in Seoul to plead for her return. After she tries unsuccessfully to speak to someone through the phone in the lobby (another symbol I’ll touch on later), Mija chases down the truck transporting Okja, hoping to stop it. The driver is an apathetic twenty-something surnamed Kim (Choi Woo-shik). His nonchalance alarms Mundo, who is riding in the passenger seat. As the truck passes under a sequence of low bridges, Mundo nervously questions whether Kim even has a commercial driver’s license. But the arrival of the Animal Liberation Front (ALF) shifts his concerns. As they enter a tunnel, the ALF disrupts traffic and releases Okja. Mundo urges Kim on to repossess the company’s property.

Mundo and Kim speak in Korean. English pulled from Netflix subtitles.

Mundo: They’re leaving! Start the truck, quick!

Kim: Fuck it.

Mundo: What?

Kim: What do I care? I’m leaving this shithole anyway.

Mundo: Huh?

Kim: You know what? I do have a commercial license, but I don’t have workman’s comp. [drops the keys to the truck out the window]

Later, as Lucy Mirando and her executive board watch news coverage of the event, Kim reappears to give an interview.

Kim and a news anchor speak in English on a 24-hour US news channel.

Kim: Yeah. Mirando is completely fucked.

News Anchor: Mirando. [looks down at ID badge] That’s your current employer, correct?

Kim: [holding up badge] Yup, but I don’t care. [shrugs] They fucked, not me. They fucked up! [points]

Kim’s character sets the tone for the presence of English in both Okja and South Korea as a whole. While Korean served as the language for Kim to complain to Mundo, when it comes time to broadcast his opinions to a global audience, he uses English. Choi Woo-shik went on to collaborate with Bong Joon-ho again when he played Kim Ki-woo “Kevin” in Parasite. English has a similarly symbolic role in the latter movie, where it serves as a salient class marker. Mija is shown teaching herself English from a book, but the high-class Park family in Parasite can pay for private tutoring to ensure their daughter’s admission into a good university. English in Parasite is the bartering chip itself, but English in Okja is the strategy behind the whole game, one where the stakes are the autonomy and agency of an entire people .

K (Steven Yeun) vividly embodies the conflict English represents to Korean-Americans in particular, and to other Asian-Americans by extension. It doesn’t seem to be an accident that K has a thick “gyopo” (overseas Korean) accent and is played by a Korean-American actor. K’s introduction makes his relationship with Korean clear:

Dialogue is in Korean. English pulled from subtitles. Emphasis added.

Kim: 뭐야? 뭐하자는 거야? [What the hell?]

K: 안녕하세요? 테러리스트 아니에요. [Nice to meet you! We’re not terrorists!]

Mundo: 뭐라고? [What?]

K: 싸움 싫어요. 안 아플 거예요. 차 멈춰 주세… 차 세워 주세요. [We don’t like violence! We don’t want to hurt you! Stop… stop the truck!]

Mundo: 쟤 뭐라는 거야? [What the hell is he saying?]

K: 차… [Stop…] [switches with irritation to English] Just cooperate, guy!

The humor in the miscommunication gets lost in the translation: K is not actually repeating the word “stop.” Both 멈춰 and 세워 mean “stop,” but only the latter is used for cars. K stumbles because he has to think about which verb is the correct one for the context, immediately revealing that he is from the U.S. and doesn’t speak Korean fluently. K’s identity as a Korean-American is critical to his role in the narrative as an interpreter. Although it doesn’t come through in the subtitles, K’s Korean is very elementary, typical of what a young child might say. He is most likely a heritage speaker of Korean who heard the language growing up, but didn’t acquire it fully. For heritage speakers, the transfer of language between parent and child is disrupted by assimilationist forces that value English more than any other language.

Despite his halting Korean, K is thrust into interpreting for the ALF. He is the only Korean member shown—the only person of color at all. Compared to the professional interpreter who accompanied Dr. Johnny to see Mija, K’s interpreting is laughably basic, as displayed when he attempts to interpret the ALF leader Jay’s message to Mija.

Jay: [to K] Shh. Can you translate? [to Mija] My name is Jay.

K: 쟤는 제이. 나는 케이라고 해. [He’s Jay. My name is K.]

Red: I’m Red.

Silver: Silver.

Blond: I’m Blond.

Mija: 난 미자예요. 얜 옥자. [I’m Mija. This is Okja.]

K: I’m Mija. This is Okja.

Jay: We are animal lovers.

K: 우리 동물 사랑해. [We love animals.]

Jay: We rescue animals from slaughterhouses, zoos, labs. We tear down cages and set them free. This is why we rescued Okja.

K: 우리 그, 도살장 그, 실험실 부수고 동물들 빼내는 거야. 그래서 옥자도 거기에서 빼냈어. [We tear down and take animals from, umm… slaughterhouses and, um… laboratories… That’s why we also took Okja.]

Mija: 정말 감사합니다. [Thank you very much.]

K: Thank you very much.

Jay: For 40 years, our group has liberated animals from places of abuse.

K: 우리 맨날 해. [We do this every day.]

Jay: Is that it?

K: Yeah. Go on.

Jay: It’s very important that she gets every word.

K: It’s all right. That’s it.

Jay: We inflict economic damage on those who profit from their misery. We reveal their atrocities to the public. And we never harm anyone, human or nonhuman. That is our 40-year credo.

K: 우… 우리는… 어… 괴… 동물 괴롭힌 사람들 싸우고… [We… We… umm… fight people that bo… bother animals…] What was the second thing you said?

Jay: We reveal their atrocities…

K: Oh, yeah… 동물 학대 다 폭로하고. 그렇지만 투쟁할 때 사람들 절대 안 다치는 거 40년 전통이야. [We expose all animal abuse, but when we fight, we never hurt people. This is our 40-year tradition .]

Despite the scene being played as humorous, as illustrated by Jay’s incredulous “Is that it?”, this is the exact position heritage speakers are put into, especially the first generation born in the US. I myself am part of that group. As a second-generation Chinese-American, I’ve found myself interpreting for my family ever since I was a child. Though my Mandarin was imperfect, I did my best to translate, even when the information was medical or legal. But there is a pressure there, too, to be a link between groups and to be a peacemaker, one that I rarely see acknowledged in fiction. K’s character deeply embodies the conflict of negotiating a hyphenated identity in an assimilationist society.

The next few moments show that pressure in action. Jay asks whether Mija knows where Okja was being taken. K shows Mija photos of the lab where Okja was created as Jay explains that everything she’s been told about the superpigs is a lie. He then tells her that they will only go forward with their plan for Okja if Mija consents, sparking a small debate among the ALF members about whether they’d truly abandon the plan if Mija doesn’t give her consent. Jay rebukes them, then continues on with his spiel.

Jay: Well, if that’s how you feel, call yourself something else and not the ALF, and get out of this truck. In order to expose Mirando, we need video from inside the lab. And this is where Okja comes in. The Mirando scientists are dying to run tests on her in their underground lab. Their star super pig, which is why we’ve made this. It looks exactly like the black box on her ear, right? Only this one can wirelessly send a video feed to us from inside the lab.

K: 옥자가 몰래카메라 되는 거야. 몰카. [Okja will become a “molka ”—a hidden camera.] [goes up to Okja] Hey buddy, shh, hi. Okay.

Jay: I’m sorry, but this was our plan. Rescue Okja, replace the black box, and let Mirando retake Okja.

Mija: 그러니까 옥자를 미국으로 데려가야 된다고요? 실험실로? [So what you’re saying is that I have to let them take Okja to America? To the laboratory?]

Jay: Yes, but don’t worry. They won’t dare hurt her. She needs to be perfect for their beauty pageant. Whatever tests they do on her in there will need to be harmless. We have a detailed plan on how to rescue her from the event in New York City. We promise to bring her back to you. If our mission succeeds, we’ll be able to shut down Mirando’s superpig project completely. And we’ll be saving millions of superpigs like Okja from death. But we won’t do it without your approval.

K: 만약에 허락 안 하면 작전 안 할 거야. [If you don’t give us your permission, we won’t go through with the mission]

Jay: What is your decision?

K: 어떻게 하고 싶어? [What do you want to do?]

Mija: 옥자랑 산으로 갈래요. [I want to go to the mountains with Okja.]

K: [presses his nail into his finger away from the others’ view] She agrees to the mission.

Silver: Thank you.

Jay: [exuberantly] This… this is a giant leap for animal kind. Thank you.

The shock to the viewer comes from the deliberate mistranslation. Here, too, we can see the symbolic relationship between Korean and English, and thereby between South Korea and the United States: Although the ALF is ostensibly asking for Mija’s consent, they can only understand her decision when it is conveyed using English. Translation is not an automatic process, and it is not even remotely close to being perfected by machines. K isn’t a neutral and passive converter of meaning. He is a human being subject to the pressure of the situation in which he is embedded. Given the ALF’s internal argument moments before about whether they’d truly abandon the mission if Mija didn’t give her consent, K is put in a position where he alone is the unexpected arbiter of Mija and Okja’s fates—a heavy burden for anyone to bear, let alone a new recruit eager to prove himself.

Later, the ALF witnesses the abuse Okja faces in the lab. Horrified, K admits that he mistranslated and tries to provide a justification, only to be harshly punished.

Jay: [places a hand on Red’s shoulder] I know it’s painful. But we can’t be weak.

K: [pressing his nail into his finger]

Blond: That’s right. This is why we need to stay focused. This is why we need to stick to the mission.

Jay: The little girl trusted us with Okja. We have to respect her bravery.

K: She never agreed to send Okja.

Blond: What’d you just say?

K: [sighs deeply] She was in our truck. She said, “옥자랑 산으로 갈래요”—“I wanna take Okja back to the mountains.” I lied.

Red: God.

Jay: Why did you lie?

K: I don’t know. In that moment, it’s just… I couldn’t… I couldn’t stop the mission. You know, this is the coolest mission ever. I have all this stuff and—

Jay: Hey, K… K. Shh. It’s okay. [slams K’s head against the desk]

Silver: [yelps]

Jay: [as he kicks and punches K, who is curled up on the ground and backed up against a wall] I hold you dear to my heart, but you have dishonored the 40-year history and meaningful legacy of the Animal Liberation Front. You have betrayed the great minds and brave fighters that have preceded you. [shakes index finger at K] Never mistranslate. Translation is sacred. From this moment on, you are no longer a member of the ALF. You are permanently banned. Get out. However, since it is vital that we continue with our mission, we will return your equipment to you after its completion. Consider this your final contribution to the ALF.

Jay is unwilling to force a mission on Mija without her consent, and he emphasizes as he introduces the ALF that “[they] never harm anyone, human or nonhuman.” Yet all that respect for ethics and life disappears when K purportedly betrays their mission. Rather than letting himself feel the full horror of being complicit in Okja’s abuse, Jay offloads that guilt onto K and strips him of his power and resources, as symbolized by his equipment. He justifies the seizure of K’s property as for the sake of the greater good.

K’s story doesn’t end there, though. As the movie progresses, Jay appears to realize the wrongfulness of his actions and to show remorse. Without K as an interpreter, Jay has to do the work of learning and using Korean. When he reunites with Mija in New York, the previously verbose Jay falls silent as he holds up a series of bilingual signs:

SORRY

미안함FOR EVERYTHING

모든 것이WE WILL RESCUE OKJA FROM THE STAGE

우리가 무대에서 옥자를 구출할거야WHEN WE DO

우리가 구출할 때DON’T LOOK BACK

뒤쪽을 보지마AT THE SCREEN BEHIND YOU

니 뒤에 있는 대형 화면을WE LOVE YOU

너를 사랑해

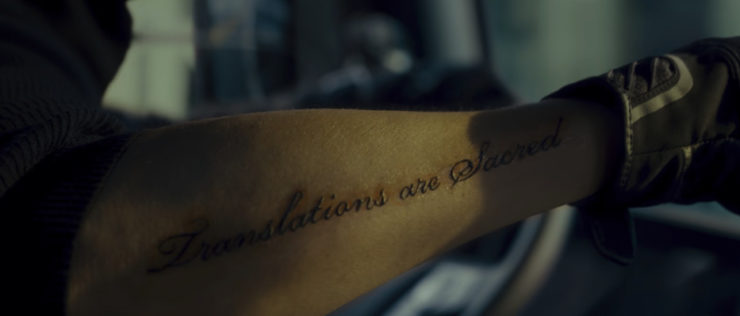

The turning point here comes from Jay seeming to realize that language is not just a resource to be exploited as he exploited K, but a tool to build bridges and foster more genuine connections. Jay puts his life on the line to rescue Okja. When he’s rescued in turn, the driver of the getaway truck turns out to be K, who shows him his new tattoo: “Translations are Sacred.”

I believe that the mismatch between K’s tattoo and Jay’s words is deliberate. After all, K has no problem remembering a complex phrase Mija said to him in Korean; it doesn’t seem likely that he would misremember Jay’s parting words. I’d like to take this tattoo, then, as another symbol channeling Okja’s deeper message. Unlike English, Korean does not distinguish between singular and plural. So, in Korean, “translation is sacred” and “translations are sacred” would both be expressed using the same sentence. But that is not the case in English. K’s tattoo calls out the fact that translation involves choice, that interpretation is just that—one possible manifestation of meaning. In treating “translation” as singular, Jay presumes a linguistic ecology that predicates itself on one truth, one voice. Translation is a singular process to him. But K, who has had to travel between multilingual spaces with all the awareness of how fraught that can be, openly brands himself with a different take of that underlying meaning. For K, translation is now a polyphonic process, one that involves multiple voices, multiple languages, and multiple configurations. He doesn’t brand himself with Jay’s words—he brands himself with a subversion of Jay’s words.

K pleads with a nurse to treat Jay’s grave injuries in the van. It may seem contradictory for him to save the very person who enacted violence on him in the first place, yet that is what Asian-Americans must do on a daily basis. Legislation extending back to the 1800s has sought to exclude Asians from immigrating lawfully to the United States. Hmong-, Cambodian-, Laotian-, and Vietnamese-Americans are among those who have had their lives disrupted by the U.S. sowing war in Southeast Asia. Despite countless examples of the U.S. showing that it is perfectly happy to exclude and annihilate us, we still live in the United States. We are dependent on its existence for our own, with all the complicity and trappings that that entails.

While K confronts the viewer with the non-neutrality of language and translation, the linguistic nature of Mija and Okja’s relationship is entirely hidden from the viewer. We never hear what Mija whispers into Okja’s ear. Still, Bong Joon-ho builds up an intimacy between Mija and Okja that shows their understanding. Phones serve as a powerful mediator of their relationship. A phone first appears in Okja when Mija attempts to enter Mirando’s Seoul office. She pounds on the glass doors and asks if the receptionist knows where Okja is. The receptionist’s only reply is to mime for Mija to use the phone in the lobby to dial in. But when Mija picks up the phone, she gets caught in an endless string of automated messages while the receptionist places an actual call to security. The phone is a symbol of communication, one that can then be controlled: Mija becomes trapped in the formalities of trying to enter Mirando’s corporate world the “proper” way. She quite literally faces off against gatekeeping. When the appropriate channels don’t work, she ends up breaking in to the headquarters.

Throughout the movie, Mija insists for people to let her speak to Okja, even asking for the phone to be put up to Okja’s ear. No one takes her seriously when she makes the request. But when the animal abuse footage triggers Okja while she and Mija are on stage, there is a moment when Okja appears to be on the verge of grievously injuring Mija. Then, Mija murmurs something into Okja’s ear, grounding her and hauling her back from a sea of traumatic memories. The two do indeed have a language that very well could be transmitted over a phone: a mother tongue shared in an intimate family space, a language that is invalidated by those who deny its legitimacy, to the point where the language is suppressed as a form of communication and expression at all. English as a linguistic empire has had that effect. Its hegemony as the world’s lingua franca and the language of global business pressures the colonized and the marginalized to adopt it over their own heritage languages, thereby divorcing us from our roots—and destroying indigenous cultures in the process.

Nowhere is English’s value as a coldly utilitarian tool of business more salient than in the ending scene, wherein Mija bargains for Okja’s life. Throughout the entire movie, others have spoken for Mija, whether the ALF with a pro-animal rights agenda, or Mirando forcing Mija to whitewash her experiences into palatable propaganda. Once again, when viewed as symbols and metaphors, this tug-of-war is not about animals at all: it is about control over what to do with “meat,” or the bodies of the colonized. In my reading, the ALF is just one manifestation of Western movements that fail to account for intersectionality. In a sense, the ALF is like White feminism: supposedly for the greater good of all humanity, even while its actual tactics don’t account for, and indeed exploit people of color. Mirando, meanwhile, is a more straightforward manifestation of the brutal capitalism and consumerism espoused by the United States. Success manifests as business prowess, and anyone who seeks to negotiate must learn the language of global capitalism and imperialism—English.

Pigs recur as a symbol for resources—and not just superpigs. At the very beginning of the movie, Mija takes deep offense when her grandpa offers her a pig made of gold as a consolation for Okja being taken away. Spurred on by her rage over the betrayal, Mija smashes her piggy bank to gather the funds to go to Seoul. Although she is loathe to see the golden pig as a dowry, as her grandfather described it, she still understands its value and carries it with her in a fanny pack. East Asians are often stereotyped as clueless tourists—another manifestation of the perpetual foreigner, albeit from a different angle—and no item of clothing embodies the tourist more than the fanny pack. It is a marker of travel and being outside of one’s native context. A few lines in the dressing room scene make me suspect that the fanny pack was an intentional choice:

Jennifer: Hey! Oh, how’s everyone doing?

Wardrobe: [tugging at fanny pack] Still with this thing. It looks super tacky.

Mija: 아, 건드리지 마요! Don’t touch it.

Interpreter: 네, 네, 네. 패니 팩 괜찮아. [Yes, yes, yes. The fanny pack is fine.] [holds up Mija’s English instruction book] I think she understands some English, so we should be careful with what we say.

In the penultimate scene, Mija shows that she has mastered enough English to negotiate with Nancy Mirando (Tilda Swinton) as she desperately tries to rescue Okja, who is about to be slaughtered.

Mija: [holds up photo of herself with Okja to a Spanish-speaking factory line worker]

Worker: [hesitates as he holds a bolt gun to Okja’s temple and looks from the photo to her]

Nancy: [appearing with a group of people] This what caused the alarm?

Frank: I believe so.

Nancy: I’m flummoxed that security is so lax as to allow a bunch of hooligans to delay the production line for even a second.

Frank: It won’t happen again. Please note that Black Chalk was here exactly on time.

K: [while being apprehended] No, guys, guys, this is—

Jay: Please, don’t touch her! Sir, sir, put the gun down, it’s okay.

K: Stop! Less violence! No! No violence!

Nancy: Isn’t this Lucy’s beloved fearless pig rider?

Frank: She is. And that’s our best superpig.

Nancy: Well, what’s the hiccup? Why is it still alive?

Mija: [in English] Why do you want to kill Okja?

Nancy: Well, we can only sell the dead ones.

Mija: I wanna go home with Okja.

Nancy: No, it’s my property.

K: You’re a fucking psychopath.

Jay: You should be ashamed of yourself.

Nancy: Fuck off! We’re extremely proud of our achievements. We’re very hardworking businesspeople. We do deals, and these are the deals we do. This is the tenderloin for the sophisticated restaurants. The Mexicans love the feet. I know, go figure. We all love the face and the anus, as American as apple pie! Hot dogs. It’s all edible. All edible, except the squeal.

Okja: [squeals loudly]

Jay: So you’re the other Mirando.

Nancy: And you are?

Jay: Let Mija and Okja go.

Nancy: Why?

Jay: You already have a shitload of money.

K: Please.

Nancy: This is business.

Jay: [while being taken away] Hey, Nancy! I hold all creatures dear to my heart, but you are crying out to be an exception. Mija!

Nancy: [dismissively] Oh, okay.

Frank: [to the worker] Termínalo.

Worker: [presses bolt gun to Okja’s temple again]

Okja: [squeals]

Mija: [in Korean] No, wait! [unzips fanny pack and takes out gold pig]

Nancy: [takes off her sunglasses, revealing an intense stare]

Mija: [holds out gold pig and switches back to English] I want to buy Okja. Alive.

Nancy: [smiles slowly]

Mija: [tosses over gold pig]

Frank: [picks up gold pig and dusts it off before handing it to Nancy]

Nancy: [bites pig to test gold] Hmm. Very nice. We have a deal. This thing is worth a lot of money. [pockets gold pig and puts sunglasses on again as she walks away with her entourage] Make sure our customer and her purchase get home safely. Our first ever Mirando superpig sale. Pleasure doing business with you.

Frank: Libéralo.

Worker: [frees Okja from her restraints]

Lucy and Nancy, being twins, are also two sides of capitalism as it manifests in the United States: Lucy represents White fragility, while Nancy represents White supremacy. Both display a strong need to control the narrative of Whiteness, whether through marketing and propaganda, or through reframing the Mirandos’ narrative as one of hard work, meritocracy, and bootstrapping, rather than the truth: Lucy and Nancy’s father made the Mirando fortune by manufacturing Agent Orange. Furthermore, as Jay calls out, the Mirandos have more than enough money. But profit is not the true motivation behind their business. Instead, the motivation is power, agency, and control. In explaining where parts of the superpig go, then, Nancy is commenting on the deeper crime represented in Okja: All parts of the colonized can be repackaged for consumption. Only our voices cannot be.

Ultimately, the ALF also reveals itself as another branch of U.S. imperialism and paternalism, a Western- and U.S.-centric approach to rights and discourse. K and Jay continue to speak over Mija until they are forcibly removed from the conversation. Only then can Mija, the actual victim along with Okja, speak for herself. She uses the colonizer and imperialist’s customs as a means to an end. The conclusion is almost absurd—there would have been no peril at all if Okja had simply been purchased from Mirando in the first place. Yet the entire ideology of Okja being purchasable is itself a deeply colonial notion, one that reveals capitalism’s inherent need to enslave people, whether through chattel slavery, indentured servitude, or prison labor. Still, Mija knows she must “speak the language” of those in power to have any hope of escaping from the institutional oppressions she’s been roped into.

As Mija and Okja walk away from the meat processing plant, a couple superpigs squeeze a tiny superpig baby through the fence. Mija and Okja successfully smuggle the baby out without anyone noticing. In my reading, the superpig baby is a representation of the chasm that is coloniality’s legacy on diasporas: the cultural link between parent and child may be preserved on an individual level, but the fact remains that hundreds more are left trapped in a system that perpetuates their status and culture as consumable, even disposable.

Despite all the trauma and devastation Mija and Okja have experienced, though, the ending is hopeful. For the only time in the movie, we hear Okja speaking to Mija, who smiles. Okja and the baby pig join Mija and her grandpa for a family meal in silence. I see this ending as a suggestion that family reunification and the ability of the marginalized to speak for ourselves is what leads to peace. Away from the trauma of the capitalist machine that seeks to dissect us into packageable, digestible parts, safety can exist.

Taken as a whole, I read Okja as a story that reveals the atrocities inherent in linguistic assimilation, even as it acknowledges that the ability to use English can be a tool of liberation for the marginalized. As a sociolinguist with a vested interest in World Englishes, I extend the ending out further to envision a pluricentric world where there are multiple voices in conversation. “Translations are sacred,” after all, is predicated on a deeper assumption: that there are multiple narratives to be translated, and multiple people to do the work. White supremacy and coloniality’s greatest strength is their ability to divide and conquer. Rather than the diaspora and the sourceland arguing over whether a particular media representation is “authentic” to an inherently diverse experience, we can ally with each other to create a transnational conversation that critiques and dismantles coloniality, imperialism, and capitalism from all sides. There is no need to wait for Hollywood to catch up. We blaze this trail for our own.

Acknowledgements: Many thanks to Rachel Min Park, who provided English translations for lines originally in Korean, as well as invaluable linguistic and cultural insight. Any remaining errors are mine alone.

S. Qiouyi Lu writes, translates, and edits between two coasts of the Pacific. Aer fiction and poetry have appeared in Asimov’s, F&SF, and Strange Horizons, and aer translations have appeared in Clarkesworld. Ae edits the flash fiction and poetry magazine Arsenika and runs microverses, a hub for tiny speculative narratives. You can find out more about S. at aer website or on Twitter and Instagram @sqiouyilu.